The theory behind stock options is quite sound. That is, options are a form of de facto stock ownership that should provide managers strong incentive to focus on operating the business in a way that would maximize shareholder value. Unfortunately, in practice stock options suffer from four fundamental flaws that subvert this basic premise:

1. option holders have limited financial risk,

2. options holders often profit from sub-par performance,

3. short vesting periods encourage a short-term business focus, and

4. options are blunt incentive/retention tools.

Close examination of the impact of these structural flaws combined with a dearth of corroborative evidence tying option use to long-term value creation have led us to the conclusion that stock options as they are structured today simply do not work. Therefore, we have reluctantly decided to vote against all stock option plans. Over the balance of this paper, we discuss the aforementioned fundamental flaws and detail how each works to prevent stock options from fulfilling the promise of enhancing long-term value creation.

FUNDAMENTAL FLAW #1:

Option Holders Have Limited Financial Risk

Stock option proponents passionately argue that options place senior executives in the same financial camp as long-term shareholders. After all, both option holders and shareholders benefit from stock price appreciation and are penalized by declines in the price of the stock…right? Well, not exactly. While it is true that both option holders and shareholders benefit from stock price appreciation, they are not equally at risk to declines in the price of the stock.

Remember that an option confers the right to purchase stock at a fixed price, a.k.a. the exercise price. However, corporate employees and directors do not pay for this valuable right. Additionally, if the stock declines in value, option holders are not required to exercise their options, i.e. purchase stock. They simply let them expire. Since option holders put no personal capital at risk upfront and there is no future obligation to invest, option holders have no financial downside.

In contrast, shareholders assume significant financial risk when they purchase a company’s stock. Because shareholders exchange cash for their ownership position, they can actually lose money if the stock declines. Ultimately, shareholders only benefit if the total return from holding the stock exceeds the rate of return required to compensate them for the potential loss of principal plus the opportunity cost of foregoing other investments.

The difference in financial risk assumed by option holders and shareholders is evidenced by the change in behavior that occurs after options are exercised. In our experience, the vast majority of option exercises are followed by the immediate sale of all the exercised stock. This behavior suggests that option holders recognize the difference in financial risk between options and direct stock ownership and typically act swiftly to eliminate that risk by converting their holdings to cash.

Some option proponents contend that the lack of financial risk for the option holder is irrelevant, because the issuing company incurs no cost. There is no cash outlay and therefore no cost to the business, so the argument goes. We beg to differ. The company (and by proxy the existing shareholders) incur a clear economic cost when an option is issued. Focusing on the lack of cash outlay from the option grant obfuscates the value transfer that occurs. The issuance of an option clearly confers a valuable right to purchase stock at a fixed cost. This right represents a real claim on the future cash flows of the business.

One final counter argument we often hear regarding the absence of financial risk to options holders relates to options as part of an overall compensation package. These option proponents contend that option holders do indeed have financial risk, because they are accepting option grants in lieu of additional cash compensation. In other words, option holders have essentially put a portion of their cash compensation at risk by agreeing to substitute options. We give little credence to this argument given there is scant evidence of corporate executives in the United States being under-compensated on a cash basis (salary plus cash bonus).

FUNDAMENTAL FLAW #2:

Option Holders Often Profit From Sub-Par Performance

As Warren Buffet has opined, “Options are simply royalties paid on the passage of time.” In other words, virtually all options vest on the passage of time as opposed to the achievement of corporate goals. This fundamental disconnect between option vesting and performance goals often leads managers to reap significant rewards for sub-par performance. The simple example outlined in Exhibit 1 and discussed below illustrates this point.

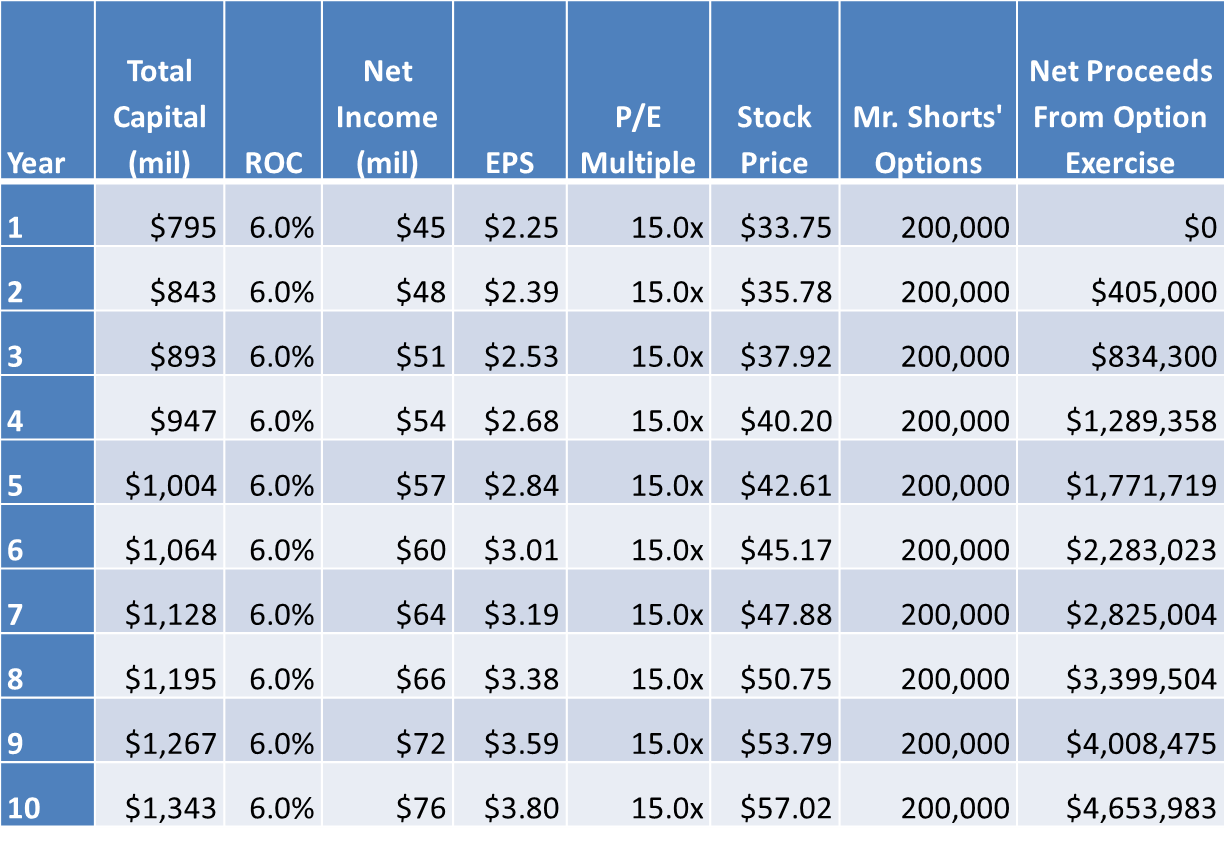

Exhibit 1: Option Value Accretion

Mr. Shorts’ option grant as % of shares outstanding: 1.0%

Exercise price: $33.75

Let us assume A.J. Shorts, CEO of Meedy Ochre Corp., receives a typical 10-year time-based option to purchase 1% of the company’s stock at the current stock price of $33.75 per share. Suppose that Meedy Ochre Corp. generates a sub-par 6% annual return on capital over the 10 years; modestly more than the current yield on low-risk U.S. Treasury notes. Additionally, the company pays no dividend. Meedy Ochre Corp. earnings per share would increase 69% over the life of the option simply for withholding earnings from the shareholders. Assuming no change in the valuation multiple, the option to purchase 200,000 shares would net Mr. Shorts approximately $4.6 million upon exercise.

In summary, Mr. Shorts earned a sub-par return on shareholder capital for 10 straight years, returned no capital to long-term shareholders (i.e, no dividends), and netted a tidy $4.6 million for his efforts. Hmmmm. This example explains why corporate managers are generally strong proponents of stock options and loath dividends, but we fail to see how long-term investors benefit from this oft repeated scenario.

FUNDAMENTAL FLAW #3:

Short Vesting Periods Encourage A Short-Term Business Focus

Because the vast majority of options vest on the basis of time (not performance), the length of the vesting period is critical. Most stock options last for 10 years, but vest fully over a period of three to four years with portions typically vesting in as little as one year. Once an option vests, the option holder is free to exercise the option and sell the shares. This short-term ability to sell stock may in fact encourage management to make decisions that enhance short-term earnings at the expense of long-term value creation in the hopes of temporarily driving up the stock price and opportunistically cashing out their options.

We believe our concerns on this front are merited given corporate executives have shown a well-documented propensity to manage to short-term earnings targets. For instance, in a survey of financial executives by Duke University’s John R. Graham and Campbell R. Harvey and University of Washington’s Shiva Rajgopal 55% of corporate managers freely admitted they would delay value-creating investments in order to meet short-term earnings benchmarks. A startling 80% indicated that they would reduce discretionary spending to meet earnings targets even though it may destroy value.

Of course there may be many reasons corporate executives focus on short-term earnings, but there is little evidence that the broad use of options has improved the situation. In fact, anecdotal evidence would suggest that the use of options has heightened this type of undesirable short-sighted behavior. Additionally, much of the value-destroying corporate skullduggery in recent years (i.e. earnings manipulation, accounting fraud, option backdating, etc) has stemmed from corporate managers’ attempts to drive up the value of their options via questionable and in many cases illegal behavior. While we cannot say with any degree of certainty that long-term vesting periods would eliminate this type of undesirable behavior, it would clearly render it less profitable.

FUNDAMENTAL FLAW #4:

Options Are Blunt Incentive/Retention Tools

To this point, we have focused exclusively on the potential for option holders to reap unjust rewards at the expense of shareholders. It is important to note that options can just as easily work in reverse by failing to reward option holders that perform admirably in their sphere of influence. While either scenario can be destructive to the interests of long-term shareholders, the point here is that options are blunt incentive/retention tools that offer no controllable link between value-creating behavior and option payouts.

This linkage problem stems from a flaw in the design of the typical time-based option. To understand this structural flaw, we need to understand the key determinants of option value: the exercise/strike price of the option (i.e. the price at which the option holder is entitled to buy the stock) and the market price of the stock at exercise.

To simplify this discussion we will momentarily ignore the short-term vesting issue discussed in the prior section and assume that option holders are inclined to hold their options for the long term. In this case, the value of the option would be closely tied to the long-term price of the stock. Over the long term, stock prices should converge with intrinsic value. This is the desired outcome from a shareholder’s perspective and therefore not a structural flaw with options.

The same cannot be said about the exercise price, which is heavily influenced by short-term stock prices. The exercise price is most often set at the market price of the stock on the date of grant. Unlike long-term company value, short-term stock prices are influenced by a myriad of factors; many of which have nothing to do with the fundamental performance of the company. Consequently, exercise prices are not necessarily indicative of the underlying value of the stock at the time of issue. Chances are good that the exercise price will be either too low or too high.

This dependence on random market values for setting exercise prices creates serious business issues for executive managers and boards of directors that favor options in their compensation/incentive structure. The unjust rewards of artificially low exercise prices are obvious, i.e. high potential to award mediocrity. The pernicious impact of inflated exercise prices are less obvious, but have the potential to be every bit as damaging to the pocketbook of shareholders. If exercise prices are too high resulting in options that are significantly underwater, the options may lose the ability to motivate altogether and perhaps even become a source of friction within an organization.

CONCLUSION

Despite the rhetoric from stock option proponents, it is our conclusion that stock options, as they are typically structured today, fail to properly align managers with long-term shareholders. Consequently, we have decided to vote against all stock option plans. It is important to note that we are not anti-compensation or against the use of equity in a well-designed incentive structure. We only ask that corporate leaders adopt a compensation system that directly ties the financial interests of management to the interests of the shareholders they are supposed to represent.